Mental Health Intervention Protocol

This document is seeking review by people who have lived experience in the area it covers, please use this form to provide feedback

More documents in need of lived experience review can be found here.

Mental health first aid techniques are used to deal with immediate crises and the risks that come from them – most often, self harm and suicide, though other issues come into play (not eating, taking unusual risks, etc). These techniques are also useful in day-to-day, non-acute situations to help people better manage distress and overwhelming emotions.

Mental healthcare provided as first aid is necessarily imperfect. In no situation will you have access to the wide variety of therapies, medications and most importantly time needed to carry out comprehensive interventions, and you almost certainly do not have the skills to carry out such tasks.

The most common interventions used in community mental health are standard medical interventions to help people function better: making sure hydration and blood sugar are not causing reduced functionality, making sure the person is warm and feels safe and cared for, et cetera.

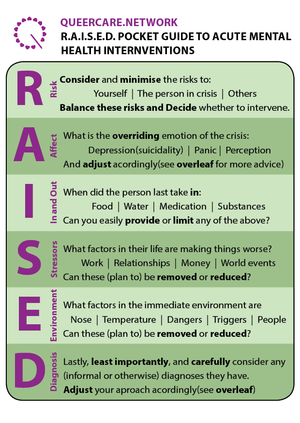

The acronym RAISED is used for mental health interventions. It should be used in a similar way to the DRABCDE acronym - to make sure that no potential issues are ignored or forgotten, and to produce reliable care - but unlike DRABCDE, in RAISED the order in which the acronym is followed is not important. You must ensure that Risk is considered first and Diagnosis considered last, but the rest can be dealt with in any order.

When we talk about a mental health crisis, we mean a situation in which someone no longer feels able to deal with emotions and experiences in the way in which they usually do.

Contents

How to use RAISED

Advice on implementing RAISED

Your job is not psychiatry: it’s to enable someone to cope as they usually do in day to day life.

To do this, you should consider everything that is inhibiting their ability to cope by using the RAISED acronym. You should react calmly and carefully, maintaining good consent. This means that you should ask for someone's permission before intervening, apart from where there is a risk to life or limb, and you should respect their boundaries around what they are comfortable doing or discussing. You must remember that what helps one person will not necessarily help someone else who is experiencing something similar.

You should use conversation as a way to keep the person you are supporting focused and to prompt them to discuss how they are feeling. Talking calmly to fill the space can reassure the person and prevent them from from spiralling into panic or depression. In especially acute scenarios, where there is imminent risk of injury, you should talk more, filling space and keeping the person focused on you. However, periods of silence can also be helpful, alongside active listening (see the active listening resource), to encourage the person to share how they are feeling. You should always adapt your approach based on what works and doesn't work for the person you are supporting.

You should ask clarifying questions to understand how the person you are supporting is feeling. Some examples of clarifying questions are: ‘I wonder…’; ‘Help me understand…’; ‘How did you learn…’; ‘What makes that so...(hard, scary)...’; ‘How would you like it to turn out?’; ‘What can we do to get there?’. You should avoid projecting any ideas you might have of how you might expect someone to cope in a situation on to the person.

Making it seem like something is being done is in itself doing something: Even if sucking a boiled sweet or completing a simple task doesn’t actually improve someone's cognitive ability, the feeling of control they gain from doing so is often sufficient to help them cope with their stressors.

If possible, you should offer ongoing support to cope with their problems, but must not offer support which you cannot provide. For example, in a protest situation, “we’ll make sure you’re safe and clear of the demo” might be in your capacity, whilst “we’ll make sure you’re safe in the long term” may not. Be honest and open.

RAISED

Risk

First, consider Risk.

It should be emphasised here that people in distress are very rarely physically or psychologically violent, and that this is a stereotype pushed by an oppressive media culture.

Carry out a scene survey and check for physical dangers and then consider psychological risks. In situations like these you must consider and balance the risk to yourself, the risk to the person experiencing crisis and the risk to others.

When considering physical dangers you should assess whether it would be more appropriate for you to move to a different location before going through the other steps in RAISED. For example, if you are on a demonstration and a person is having a uncomfortable time and crying, and at the same time there are riot control agents in the area, you should decide to check up on the person after you have moved to an area free from contamination (after checking for physical problems which may be causing distress).

When considering risk to yourself you should think about whether supporting the person who is experiencing distress will seriously damage your mental health - this may be because their distress is caused by an issue which you have experienced, and/or because you are particularly tired or in a poor space mentally. In this case you should pass off to a buddy or other carer.

When considering risk to the person experiencing crisis you should think about the support systems the person experiencing distress has, such as whether or not there are others who can care for them, and risks they may experience as a result of their distress (such as risks of self-harm, or harm from the medical or legal systems).

When considering risk to others you should think about the risk to the mental health of other people who may care for the person experiencing distress if you do not support them, or anyone else who may be less able to cope if the person reaches out to them. You should also consider whether the person has caring responsibilities towards others which they may struggle to meet if they don't get support.

You should balance these risks so that you and/or others can support the person in crisis as safely as possible. For example, if you know that supporting someone will make you feel tired and upset, but if you don't support them they will reach out to someone else who is likely to become very distressed as a result of caring for them, you may choose to support them yourself. In this situation you should make sure to think about your own support systems and coping strategies to help you after you have done this care.

Buddy format in mental health interventions

The ideal format for doing mental health interventions in less strenuous settings (“in the community”) is in a group of three people. Mental health interventions are often extended, and it is beneficial to have the ability for one person leave for a while to take a break (or to sleep, as interventions are often late at night), to get food, or to make a warm drink, whilst still maintaining a buddy pair who can check each other's work and make sure the person in distress is safe. This format can be replicated for virtual care, which is done online, over messaging or video call apps - a group chat or call with two or three carers as well as the person experiencing distress is less likely to lead to burnout amongst the carers.

In a protest situation, you will probably be working in a buddy pair, and given that interventions in a protest are generally faster, this is generally fine.

Affect

Affect is about ascertaining a person's general mood and what the shape of the problem is. This most usually breaks down into panic or depression, or some combination thereof. In this step you should also consider whether a person is perceiving a different reality to you - see Supporting people perceiving a different reality to you protocol.

If someone is depressed or suicidal, help them build a future in which they can see themselves. Talk about future plans and act as thought it is assumed they will be around to take part. Reassure them that the problems they are experiencing can be dealt with and make plans for dealing with them together if this is something you are confident you can support with.

If someone is panicked, reassure them of their safety and their support system and offer assistance with their Stressors if you can provide it. Do not minimise their problems, but assure them that they are up to the task of dealing with them.

If someone is experiencing sudden emotional swings, respect their feelings in the current moment and accept that they are real emotions, not 'fake feelings' or equivalent. Use non-judgemental language and deal with feelings as they come. If someone is expressing opinions that they don't usually have and/or which you don't share, you can validate the emotion without validating the opinion, for example by saying 'I can see that this is making you feel [frustrated/angry/upset/excited/etc.]'.

If someone is nonverbal, provide time and space, reduce possible stressors, and offer a pen and paper or digital notepad to pass messages.

On a demonstration you are anecdotally more likely to run into panic than depression, but you should not make assumptions.

In and Out

Similar to the CSAMPLE step “Last in and out”, this is one of the most (possibly the most, following Risk) important things to consider in a mental health intervention.

The most common factors exacerbating mental health crises encountered by QueerCare are low blood sugar, missed medication or a lack of hydration.

Low blood sugar is very rarely the root cause of the crisis - this is more likely to be previous trauma or chronic mental health conditions or many other issues - but what makes the person unable to cope with this cause as they usually do in day to day life is impaired cognition as a result of low blood sugar. A common cause of this is people not eating sufficient meals.

Most QueerCare kits include easy to use sweets for countering low blood sugar. Not only does the act of eating something serve to give the person a feeling of control that is frequently lacking and a distraction from the issue at hand, but when using boiled or similar sweets, glucose is absorbed directly into the bloodstream through the mucus membranes in the mouth, rapidly bolstering a person's functionality and thus ability to cope with their situation.

Please note that giving someone something to eat may not always be appropriate, such as if someone is experiencing sensory overload or an eating disorder crisis and this would make their distress worse. In these situations you should consider other steps in RAISED that can be taken to increase the person's feelings of agency and control over their situation. Please see the supporting people experiencing disordered eating protocol for specific guidance on this.

It is also advisable to have water in your kit or when doing an intervention: dehydration has a similar effect on cognition to low blood sugar.

This step also encompasses any medication or other substances the person has taken - not only mental health medication, but, for example, painkillers, which can both inhibit cognition or the lack of which can have a person in pain, or non-medical substances which can cause changes in emotion or perceptions of reality.

On demonstrations, people frequently skip breakfast and then run around the streets for several hours, causing mood dips and difficulty thinking clearly. When combined with stressors this can easily cause a mental health crisis.

The "out" section mainly comprises two things: If a person has impaired bowel function, this can cause significant discomfort, exacerbating and/or causing a mental health crisis. And iff a person has not urinated for a long time, this is a sign of dehydration.

Stressors (and Sleep)

At this stage, consider what stressors are acting upon a person. If they can cope in day to day life, what's changed here? Is there an exam coming up? Bad news? Relationship issues? Recent experience of violence? Use your knowledge and active listening skills to determine what the Stressors are, and consider suggesting ways you can work together to make them less of an overwhelming issue. Don't minimise someone's Stressors, but help them to feel assured that they are up to the task of dealing with or working through them.

In this stage you should also consider how much sleep the person you are supporting has had recently, as well as the quality of their sleep, and whether this is impacting their ability to feel able to cope.

Environment

Look for factors in someone's environment (physical or otherwise) which are causing their mental health to be worse.

These factors are often especially important for people who have sensory issues and you should consider all five senses (sight, sound, smell, taste and touch) as well as specific combinations, such as a triggering person or disturbing event in proximity.

Common factors in the environment include:

- Bright sunlight or lights

- Pitch black or very dark rooms

- Flashing or strobing lights

- Triggering or difficult smells

- Loud music

- Sharp bangs or cracks

- Scratchy, uncomfortable or restrictive clothing

(When considering taste, people will often mention a bitter taste - this is a common symptom of a panic attack)

When you've worked out potential factors causing someone to be less able to cope than normal, either remove them from the area or remove the factors from their vicinity: move to a different room, for example, or turn down loud music.

In this step you should be aware that someone may be perceiving something distressing in their environment which you are not perceiving - see Supporting people perceiving a different reality to you protocol.

Diagnosis

The most important thing to consider in this step is that it comes last.

You are, unless you have significant experience and knowledge of mental health care, not skilled or knowledgeable enough to make even tentative diagnoses and you must not attempt it. The topic of mental health diagnoses is complicated, political and often very personal for an individual.

You should be aware that a person may not wish to discuss their diagnoses, and may find questions about this intrusive or upsetting.

However, it may still be worth considering if a person has any mental health diagnoses which could be relevant to your interactions with them – for example, this may indicate that you should avoid offering food because of an eating disorder. You should treat informal and self-diagnosis as “real” as formal diagnoses for this step. Formal diagnoses are not accessible to everyone, and for various reasons may have been specifically avoided.

If you ask about this, you should do so sensitively and frame the question in a way that makes it clear that answering is optional, for example “Do you have any mental health conditions that you think I should know about?“. If you need to ask what their diagnosis entails, you should ask questions like “What does that mean for you?” and “Should I avoid doing X?

You should be careful and cautious about making any assumptions because of someone's diagnosis. Media and medical representations of diagnoses often bear little resemblance to people's lived reality. Moreover, in some cases the person may disagree with a medical professional’s diagnosis of them, or contest the validity of the diagnostic label itself. Listen to people who have the diagnosis in question and base your work on this and on your experience with the person you're caring for.

Non-Acute Situations

RAISED is most often used in acute mental health interventions, but these techniques are also useful for day-to-day, non-acute care, to help people manage their mental health.

When employing RAISED for non-acute care, you should talk to the person you care for and spend time discussing what they find helpful and unhelpful. The same steps apply:

- Risk

-

- You should make sure that your interventions will not be unhelpful either to the person you are caring for, or to you yourself.

- You should make sure not to take on responsibility you don't feel able to meet.

- If the person you are caring for is likely to self-harm or attempt suicide, you should work with them to find ways to reduce the risk of those actions.

- For suicide, this probably means taking steps to prevent an attempt, identifying likely methods and making them harder.

- However, depending on the likely methods you may also need to prepare for an attempt by making sure you have appropriate first-aid supplies: e.g. clean towels or bandages if they are likely to cut themself, or activated charcoal and/or naloxone for overdoses.

- In the event that they do make an attempt, this will be a red flag and you will almost certainly need to call an ambulance; if you struggle with phone calls you can make a script in advance.

- For self-harm you should help them find safer ways to self-harm', if necessary, unless they specifically want you to help them stop. Remember that preventing their usual methods of self-harm might only cause them to find other, more dangerous ways to self-harm.'

- Affect

-

- You should discuss how you can both recognise the signs that they are finding it harder to cope.

- You can make plans in advance for how to deal with those particular affects. People experiencing distress may find it difficult to know or communicate their needs in the moment, so advance plans can help you know how best to support them.

- It is often useful to arrange times for regular check-ins.

- This can be in-person or virtual, such as on a messaging or video call app.

- You can use this to chat about how things are going, or to do another calming or distracting activity.

- In-and-out

-

- If the person you are caring for is likely to forget to eat, drink or use the toilet, you should set up reminders for these things.

- Reminders could be automated (e.g. alarms on a phone) or could involve you or someone else checking in.

- However, if they have an eating disorder, you should work with them to find a way to remind them about food and drink that is unlikely to trigger them.

- If the person you are caring for is likely to forget to eat, drink or use the toilet, you should set up reminders for these things.

- Stressors

-

- If the person you are caring for has particular things that often cause them stress, you should work with them to develop scripts or systems for making these things easier to deal with.

- If you are able to do so and it is safe, you can offer to help with these stressors when they arise.

- Environment

-

- If the person you are caring for has difficulty with certain environments, you should:

- Find out what aspects of their environment cause issues

- Ask them if their environment is okay during check-ins

- If the person you are caring for has difficulty with certain environments, you should:

- Diagnosis

-

- Remember that you are probably not qualified to make diagnoses.

- You can ask what diagnoses the person has, but remember that this might be a difficult topic.

- The diagnosis, if they tell you what it is, is the start of a conversation, not the end of one. You must not make assumptions about what this means for them - you should ask what the diagnosis means in their particular case.

In general, remember to preserve the person's agency. You're working with them, not on them.